Blaming Jews (and Only Jews) for the Arab-Israeli Conflict

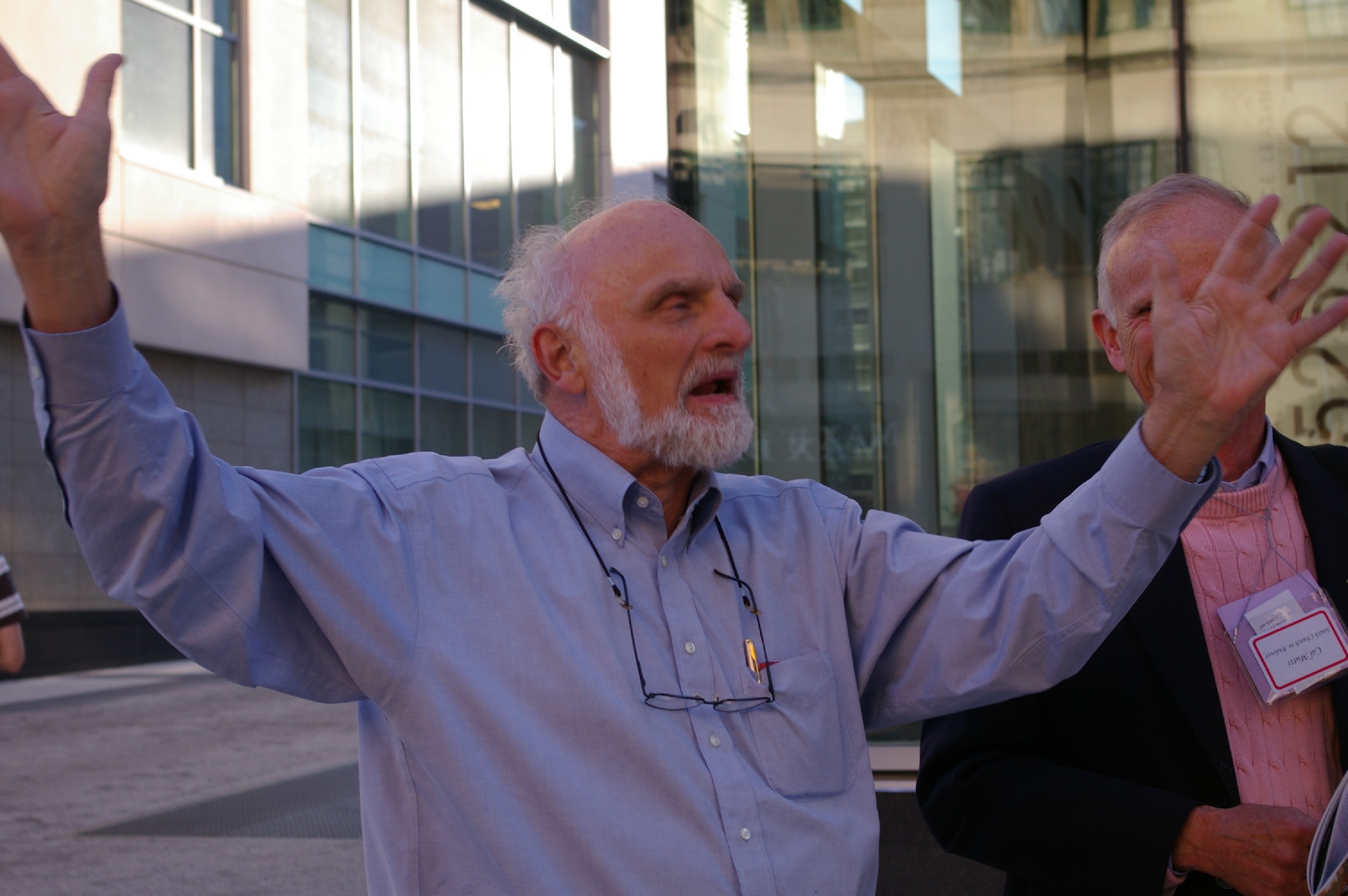

Walter Brueggemann, a giant in the world of Old Testament theology and interpretation, has affirmed the notion that the Arab-Israeli conflict is solely the fault of the Jews.

Such an assertion will be met with disbelief from admirers his work which includes David’s Truth, his commentaries on Genesis, First and Second Samuel and Message of the Psalms.

Still the fact remains that in Brueggemann’s view, Jewish self-understanding can reasonably be regarded as the root cause of the fighting between Israel and its adversaries in the Middle East.

Brueggeman, an influential Protestant theologian, makes this perfectly clear in his forward to Mark Braverman’s newly released book Fatal Embrace: Christians, Jews, and the Search for Peace in the Holy Land (Synergy Books, 2010). After attesting to Braverman’s bona fides as a “passionate Jew with a long and deep love for Israel,” Brueggemann, writes:

At the bottom of [Braverman’s] argument is the thesis, so well considered here, that it is Israel’s elemental conviction about being God’s one chosen people—and the ensuing social-political exceptionalism—that is the root cause of the conflict. It is that most elemental conviction on the part of Jews that he holds up to scrutiny and about which he insists upon a radical revision. The claim for exceptionalism—held commonly by Israel’s most one-dimensional advocates and by Israel’s most urbane critics—makes serious, realistic political thinking impossible and gives warrant for brutalizing policies carried out by the Israeli government that are destructive, self-destructive, and finally irresponsible. (Pages xv, xvi.)

By rooting the Arab-Israeli conflict solely in Jewish theology, Braverman, and by affirmation, Brueggemann, conveniently ignores the role Arab ideology and Muslim theology has played in fomenting violence against Israel and Jews in the Middle East. It’s comforting to believe that the Arab-Israeli conflict can be brought to an end with Jewish and Western self-reform. As comforting as this belief is, it requires reader to ignore one of the most troubling and enduring political realities of the Middle East: Israeli peace offers and withdrawals have been preludes to increased Arab violence. This is the reality that the Israelis have contended with for well over a decade and it surely plays a role in their response to Palestinian violence, and yet Brueggeman insist on rooting Israeli behavior solely in theology.

The notion that Jewish theology has made “serious, realistic thinking impossible” ignores the repeated Israeli efforts to exchange land for peace in the past few years, and the violent response it has received. Again, as has been rehearsed here numerous times, Israel withdrew from Lebanon in 2000 only to be attacked by Hezbollah six years later. It withdrew from the Gaza Strip in 2005 only to see an increase in rocket attacks and to be attacked the following year by Hamas.

And the Second Intifada began after Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak made an offer to Arafat at Camp David. Arafat said no and refused to make a counter offer. A few months later, Arafat said no to the Clinton Parameters (which Barak accepted) and the violence continued. These facts, which clearly undermine Brueggeman’s theological interpretation of Israeli behavior are ignored.

At first glance, Brueggemann appears to be merely expressing his objection to Jewish theology and its impact on Israeli policies, but he does a lot more than that.

In sum, Brueggeman has affirmed a Judeo-centric view of history that denies the region’s Arab and Muslim people and leaders of any moral agency. For commentators like Brueggemann (and they are legion), the Palestinians are incapable of any independent thought or action of their own, but are helpless supporting actors whose suffering speaks only to the failings of the Jewish people and their state – not to their own moral and strategic failings. In this worldview Jews are the only people in the Middle East whose beliefs and behavior have any consequence, and are therefore the only people worthy of judgment.

The schema Brueggeman affirms works like this: Everything the Palestinians do is the result of Israeli actions, which in turn are an expression of Jewish feelings of entitlement, which in turn is rooted in Jewish theology regarding their choseness.

That’s Judeo-centrism all right.

That Brueggemann subscribes to this worldview should not come as a surprise. These tendencies were evident in the second edition of The Land published by Fortress Press in 2002. In this book, Brueggemann juxtaposes the impulse to grasp for control and safety with the faith that allows people to wait in confidence for the gift of land (and the well-being that comes with it). In the chapter titled “Blessed Are the Meek,” offers this assessment of Israeli policies:

While the two symbols of Western Wall and Masada offer the contemporary state of Israel deep options for waiting in confidence or seizing in military assertion, it is clear that the contemporary state of Israel has opted for the latter, to the complete disregard of the former. As I write this, Israel, under the leadership of Ariel Sharon, is currently undertaking an aggressive brutalizing assault on the neighboring Palestinian population. That option for brutality against others in the name of God of Israel is a powerful evidence of the way in which land traditions from the ancient texts are open to a variety of readings and responses, some of which make for war and not for peaceable habitation.

Given the book’s release date of July 31, 2002, it’s reasonable to assume that when writing about Sharon’s “aggressive brutalizing assault on the neighboring Palestinian population Brueggeman is referring to Operation Defensive Shield initiated in April 2002 after a singularly horrific suicide attack that killed 30 Israelis and injured more than 140 others attending a Passover Seder in March 2002. As a result, Sharon sent troops back into cities and towns that had previously been handed over to the Palestinian Authority which had agreed, under the Oslo Accords, to stop terror attacks but instead had let these municipalities become part of a terrorist infrastructure.

If Brueggemann wants to assert in the context of the Arab-Israeli conflict that “Meekness leads to turf” (a message he offers in The Land on page 166), he needs to contend with historical realities like this. He also has to deal with physical and concrete realities that prompted Israel’s creation. European Jews did not move to Palestine in the 1930s and 40s because they thought of themselves as the chosen people but because they had nowhere else to go. No one wanted them.

Israel’s creation in 1948 answered a question that the international community could no longer ignore: Where are the Jews to live? Sixty-plus years later, Arab and Muslim extremists in the Middle East are still trying to re-open debate on this question by proffering the same answer they did in 1948: Anywhere but here.

This opposition is rooted in part in Islamic theology regarding Jews and the prohibition of allowing non-Muslims to rule over territory previously governed by Muslim rulers. Neither Brueggeman nor his followers, most notably Gary Burge and now, Mark Braverman, have, up until now, been willing to address this. (Gary Burge has a new book coming out – which Brueggemann has endorsed – and could address the issue in this text. Miracles do happen.)

It seems reasonable to ask when and if Brueggemann will direct his scholarly eye toward the Islamist theologies that have motivated so much violence in the Middle East. It is not as if he lacks for a hermeneutic to analyze and assess these beliefs. He has fashioned this hermeneutic in the course of relentlessly interrogating Jewish scripture, theology, and self understanding and using it to explain Israeli policies.

If Brueggemann can, in good conscience (and with a straight face) tell Israeli Jews that “Meekness leads to turf,” despite what they’ve experienced in the past decade, integrity demands that he offer this same kerygma to Israel’s adversaries, unless of course, he regards Palestinian violence as a manifestation of “grasping in confidence.”

More from SNAPSHOTS

Why Does a NY Times Journalist Want to Suppress an Anti-Hamas Article?

May 29, 2018

A New York Times journalist thinks the Wall Street Journal shouldn't have published an opinion piece criticizing Hamas's anti-Israel propaganda campaign. The reporter, Declan Walsh, is one of the Times reporters who has covered the [...]

Iran is Funding Hamas’s Violent ‘Protests’ at the Border, Media M.I.A.

May 22, 2018

Iran's Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khameini The Islamic Republic of Iran is behind the recent Hamas-orchestrated violent demonstrations—dubbed the “March of Return”—at the Israel-Gaza border, according to Israeli authorities. Yet many major U.S. news outlets [...]

Are Gaza Gunmen “Protesters”? NY Times Refuses to Say

May 21, 2018

After repeatedly insisting that "Israeli soldiers killed 60 protesters" during clashes last Monday, May 14, the New York Times is refusing to clarify whether its count of supposed protesters includes the eight armed Hamas fighters [...]

Bahrain Says Israel Has a Right to Self-Defense, and the Media Shrugs

May 15, 2018

Bahrain's Foreign Minister and then-U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry The foreign minister of the Arab nation of Bahrain, Sheikh Khalid al-Khaalifa declared on May 10, 2018 that Israel has a right to defend itself. [...]

AFP Captions Call Jerusalem Parade Participants Settlers

May 15, 2018

Numerous Agence France-Presse photo captions generalized all participants in Sunday's Jerusalem Flag Parade as "settlers," despite the fact that the crowd hailed from across Israel, within the Green Line, as well as outside. A sampling [...]

Journalist: Hezbollah Shows ‘More Maturity’ Than Israel

May 9, 2018

Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah A Los Angeles Times special correspondent, Nabih Bulos, declared on Twitter on May 7, 2018, that Hezbollah (“Party of God”) shows “more maturity” than Israel. Hezbollah is a Lebanese-based, Iranian-backed, [...]